In the field of real estate, contracts are made all of the time. Real estate attorneys see and write contracts for lease and sublease, contracts for sale, contracts for purchase, and other types of real estate contracts. Contracts are perhaps the physically flimsiest but practically strongest underpinning of all real estate transactions as we know them. These valuable assets provide all parties to the deal with confidence that the agreement is enforceable as written, without the need for further demonstration of commitment or other protocol.

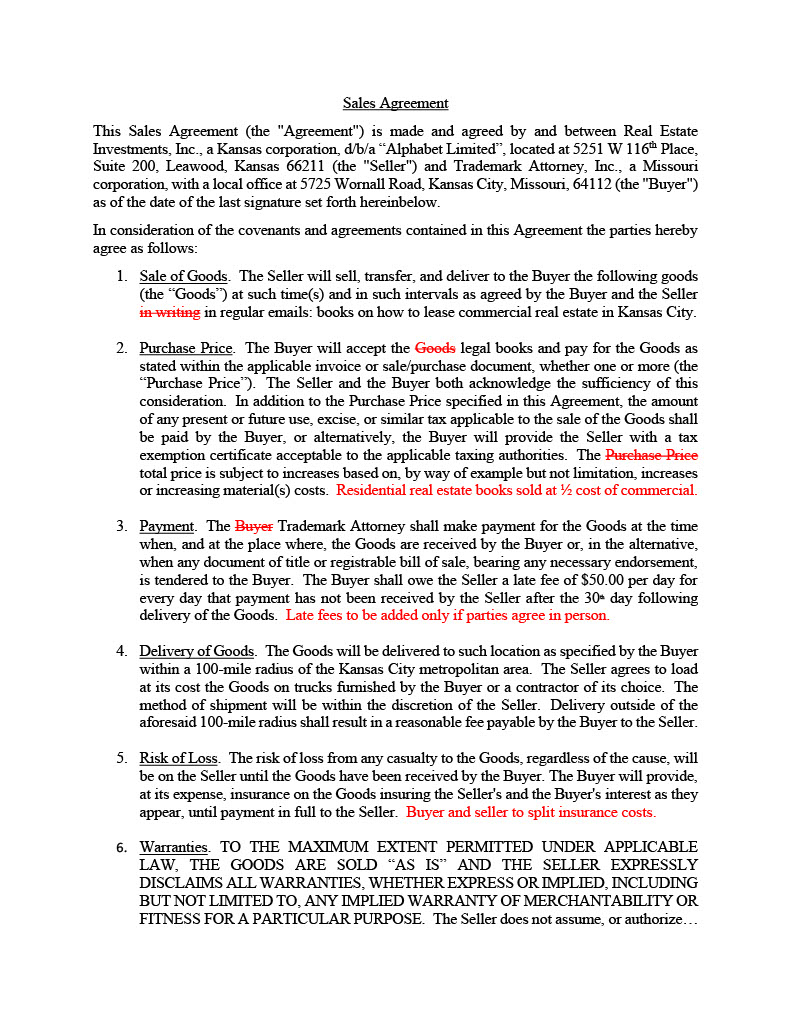

Though they may be common, and their value widely understood, written contracts are not all of equal quality or reliability. Take a look around at all of the different forms of real estate contracts available for download from the internet. Some are long; some are short; and others leave the reader wondering what she just read. While there is more consistency of form with respect to residential real estate contracts used within the Kansas City metropolitan area, there are changes frequently made to these documents, whether as updates to the form itself or idiosyncratic alterations of the contractual terms. Outside of residential real estate (such as in the realm of recreational and commercial real estate), the status quo is closer to “no two contracts are alike” than “these are the standard forms”.

The differences from document to document can serve a valuable purpose–to memorialize bespoke terms and conditions agreed to by the contracting parties, whether arising from unique relationships, custom products or services, or past dealings between or among those in privity. The use of a “one size fits all” document might be appropriate for the commercial sale of a truly commoditized, highly invariable product, but such a rigid paper is ill-suited to the distinguishable nature of real estate, where variability reigns supreme and individualized circumstances matter. With differentiation and variance, though, comes differences of opinion.

Cases involving real estate contracts in Kansas are ubiquitous. One such case worthy of review is Coble v. Scherer, 3 Kan. App. 2d 572, 572, 598 P.2d 561, 563 (Kan. Ct. App. 1979), in which plaintiffs Teddie and Barbara Coble appealed from a judgment denying them recovery of a $5,000 deposit on a contract for the purchase of real estate.

Back in 1976, Teddie and Barbara Coble saw an advertisement for the sale of real estate owned by defendants Scherer. Id. at 572-73, 563. Shortly thereafter, they viewed the property, determined they wished to purchase it, and began evaluating finances. Id. at 573, 563. Teddie and Barbara Coble, the Scherers, and the real estate agency involved in the deal signed a contract for the purchase and sale of the subject property. Id. The contract stated that $1,000 was received in part payment for purchase of the property and, via a handwritten provision, that another $4,000 cash payment would be due in about a week. Id. at 573-74, 563. Both the $1,000 and $4,000 payments were made by the purchasers, totaling $5,000. Id. at 574, 563. The balance was to be paid by assuming the Scherers’ mortgage and additional cash. Id. There was one additional handwritten provision in the contract, the meaning of which became the source of significant disagreement between the parties: “the additional aforesaid $4,000 to be considered earnest deposit.” Id. at 574, 563-64.

For one reason or another, financing fell through. Id. at 574, 564. Teddie and Barbara Coble hired an attorney who demanded that the real estate agency involved in the transaction, Jackson & Scherer, Inc., return the $5,000 down payment. Id. The real estate agency declined to return the funds. Id. Plaintiffs then sued to recover their down payment, but the court did not find in their favor. Id. at 575, 564. The plaintiffs then moved for a new trial, were denied, and then appealed. Id.

After swiftly casting away the plaintiffs’ argument that there was no meeting of the minds, and agreeing with the trial court that a contract for purchase and sale of the real estate did exist, the appeals court shifted its focus to the determinative issue before it: “whether the real estate contract as prepared by the defendant was ambiguous.” Id. The court went on to cite relevant Kansas laws as it relates to contractual ambiguity—“[w]hether a contract is ambiguous is a question of law to be decided by the trial court” and “an unambiguous contract must be enforced according to its terms[.]” Id.

Applying these laws, the appeals court found that the contractual provisions in the purchase and sale agreement were clear and unambiguous and that the trial court, accordingly, should have looked only to the four corners of the document to ascertain the forfeiture amount (whether $1,000, $4,000, or the full $5,000) in the case of breach. Id. at 576, 565. A forfeiture of $1,000 as liquidated damages was clearly contemplated, so the plaintiffs’ loss should be limited to $1,000. Id. Even if the purchase and sale contract were ambiguous, though, the loss of the plaintiffs would still be limited to $1,000 as an “ambiguous contract must be construed strictly against the drafter and liberally towards the other party.” Id. (citing Crestview Bowl, Inc. v. Womer Constr. Co., 225 Kan. 335, 592 P.2d 74 (1979)). Jackson & Scherer, Inc., the real estate agency, and also a defendant in the case, was the party that drafted the contract. Id. at 572, 563.

The court made an important point in supporting its conclusion that only $1,000 was to be forfeited by the plaintiffs. The other amount of money paid, the $4,000, was labeled as “earnest deposit”. Id. at 576, 565. Because the $1,000 was a part of the forfeiture clause stating the amount of liquidated damages in the event of a failure to make required payments beyond this initial sum, and the second payment amount, $4,000, was by a handwritten insertion “to be considered earnest deposit”, those two figures stood for different purposes. See id. (“It is reasonable to assume that two amounts with two different labels are susceptible to two different meanings.”). The appeals court ultimately reversed the judgment of the trial court and remanded the case to said court with directions to enter judgment for the plaintiffs for $4,000. Id. at 577, 565.

The Coble case sheds light on a few concepts that have broad applicability. First, Coble is a bit of an economics lesson on inflation. Going to trial over legal disputes concerning $1,000, $4,000, and/or $5,000, losing, and then appealing to a higher court might not make financial sense in 2022 absent an attorney’s fees clause or other compelling reason. In the 1970s, that quantity of money went a lot further and meant more to the average American, justifying to a greater extent attorney participation in disputes of that size. Back in 1976—the year that the contract ultimately litigated in Coble was made—the price of a postage stamp was 13 cents, a gallon of gas averaged 59 cents, and the cost of a gallon of milk was $1.68. Imagine having access to goods of those prices today! With consumer staples being so inexpensive in the 1970s, as we view them in light of their nominal prices in 2022, it becomes easier to understand how such a significant legal battle for a dispute up to $5,000 in “value” could take place.

Second, Coble teaches an important lesson about the importance of making skilled revisions to a contract. Handwriting itself may or may not be an appropriate way to make an addition or edit to a contract, depending on the time one has available, but what is certain is that modifications to a contract must fit within the framework of the original document or they risk creating ambiguity. This author has seen numerous instances of changes made to an otherwise coherent document that do not conform to the prior format or the defined terms therein. These ill-fitting changes not only damage the aesthetics of the work but also may cause two or more meanings to be construed from the work’s provisions, antithetical to the typical objectives of contracting parties.

Third, the Coble case is a lesson on the legal risk of drafting a contract. If there is ambiguity in the document, the draftsman is the one who caused or contributed to the existence of that uncertainty, so he should correspondingly bear responsibility. The non-drafting party gets the benefit of capitalizing on the drafter’s lack of clear and explicit writing. Thinking twice before putting pen to paper or using an internet-based template, especially in the absence of legal counsel, might save future woes. Those who place a premium on autonomy and prefer to do their own writing could certainly consider engaging an attorney for review purposes prior to the execution of the writing.

This Leawood, Kansas-based law firm writes, reviews, and amends real estate contracts with regularity. We have extensive experience working on commercial and residential leases and contracts for the purchase and sale of real property. We are able to help with contract-based projects anywhere in the states of Kansas or Missouri. Please contact us at 913-735-7707 or schedule with us here if we can be of service to you, your business, or your family. You may also wish to see a list of this law firm’s real estate law services or read about interpreting written contracts in Kansas on our blog.

Matthew T. Kincaid